Infinite Leverage and the Secured Lending Standard

Discussing the Secured Lending Standard and why the Federal Reserve is okay with hedge funds using infinite leverage.

In some ways, this issue serves as a Part 2 to an issue I published a month ago titled: “The Banking System Was Redesigned. Did You Notice?”.

In that issue, I discussed how the Federal Reserve deftly transitioned the US central banking system from one where reserves are scarce to one with ample reserves.

This transition was so deftly managed that most people didn’t notice.

Well, the transition to ample reserves is not the only major thing that changed for the financial system during this time.

In this issue, let’s discuss the emergence of the Secured Lending Standard that’s not only crucial in facilitating the transition to ample reserves but also in ensuring stability in this new financial system.

As a corollary, we’ll also discuss how hedge funds are surprisingly able to access infinite leverage in this new system and the Federal Reserve is apparently OK with it.

What is the Secured Lending Standard?

Before I start yapping about the Secured Lending Standard, it will be helpful to discuss why I’m even writing about it.

The Secured Lending Standard is important because it fundamentally changes how lending works in the Western global financial system.

Lending forms the backbone of this financial system, keeping money flowing and financial institutions solvent. As such, changes to how lending works changes everything.

So what did the introduction of the Secured Lending Standard change?

Put simply, major financial institutions are now significantly incentivized (and in many ways required) to lend to each other through fully-collateralized loans backed by US treasuries.

This type of loan is known as a repo (repurchase agreement).

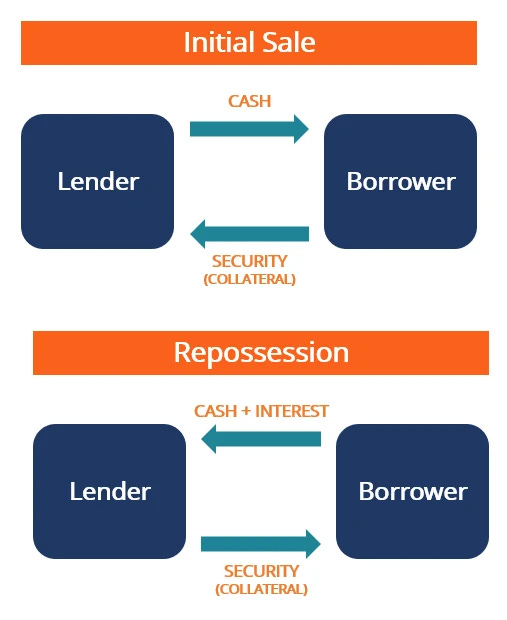

💡 Here’s how a repo works:

When a borrower wants US dollars, they establish a contract with the lender where the borrower sells treasuries they own to the lender with the agreement that the borrower will repurchase these treasuries at the end of the loan for the original amount + interest.

In this way, the borrower temporarily converts their treasuries into liquid US dollars and the lender gets a very safe loan that’s collateralized with treasuries (hence the name the “Secured Lending Standard”).

In the event that the borrower can’t meet the contract’s obligations and fail to repurchase the treasuries at the end of the loan, the lender gets to keep the treasuries.

Theoretically, this keeps any financial contagion contained with borrowers.

After the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, the Federal Reserve and the US government enacted a series of banking regulations that significantly incentivized the use of secured lending over unsecured lending.

They include:

The Dodd-Frank Act (hindering banks’ risk-taking abilities)

The Basel Framework (discouraging systemic risk and excessive leverage)

The SEC’s money market reform

Thanks to fellow finance newsletter writer Concoda for this.

Unsecured lending comprised such lending facilities as the Fed Funds Market and the Commercial Paper Market.

As the name suggests, unsecured loans were not collateralized with treasuries and thus riskier.

💡 The main takeaways from this section are:

Secured loans are loans backed by high quality collateral, such as US treasuries.

The most popular secured loan is known as a repo (repurchase agreement).

Through a series of new banking regulations after the Great Financial Crisis, repos have become a significantly popular way for institutions to obtain short-term funding.

Practical Implications of the Secured Lending Standard

Ensuring an orderly transition to the ample reserves regime

One immediate effect of the rise of the Secured Lending Standard is a significantly increased demand for US treasuries in the financial system.

This is not a difficult conclusion to reach given that loans following the standard require full collateralization with treasuries (technically other high quality debt will do but treasuries are considered the highest quality of debt). If most short-term institutional loans are backed by treasuries, then institutions have a much higher demand for treasuries.

It’s not a coincidence that the Federal Reserve started transitioning the banking system to an ample reserves regime just as the Secured Lending Standard was getting proselytized among financial institutions.

In an ample reserves regime, the Federal Reserve has to flood the system with trillions of dollars and this could potentially destabilize the value of the US dollar and US debt (i.e. treasuries).

As such, to usher in a smooth transition to the ample reserves regime, a corresponding rise in demand for US treasuries is required.

The Secured Lending Standard is perfect for this. Not only does it increase systemic demand for US treasuries, it also makes institutional lending significantly safer.

The Fed Funds Rate is effectively deprecated, but everyone still refers to it

As mentioned above, the rise of repos as a source of lending resulted in a corresponding drop in unsecured lending, which includes such important lending institutions as the Fed Funds Market.

The Fed Funds Market used to be an incredibly important source of lending in the system and that’s why the Federal Reserve still targets the Fed Funds Rate to implement short-term interest rate policy, even though the Fed Funds Market’s volume today is minuscule relative to repo volume.

Even as the Federal Reserve and financial media continue to refer to short-term interest rate policy as targeting the Fed Funds Rate, the most important short-term interest rate now is SOFR or the Secured Overnight Financing Rate.

SOFR, not surprisingly, is an aggregate measure of repo rates across the financial system.

One wonders when the Fed will start to officially target SOFR in its short-term interest rate policy rather than the Fed Funds Rate. Practically, this is already the case and it’s simply an exercise of marketing and copy-writing for SOFR control to be the official central bank policy-du-jour.

☕ If you’ve found our work helpful or informative, consider treating us to coffee by upgrading to a paid subscription. Thank you!

🙏 This is a passion project at the perfect intersection of our interests. We love writing and we love finance.

Infinite Leverage?

In a note published in September last year regarding hedge funds and the repo market, the Federal Reserve wrote this:

”As shown in Table 1, this capital amount was $9.88 billion as of December 2022, which implies that hedge funds in the aggregate were effectively leveraged 56-to-1 ($553 billion / $9.88 billion) on their Treasury repo trades, though individual funds facing zero haircuts did not require any capital to support their repo borrowing and were effectively infinitely leveraged on these trades.”

I found the Federal Reserve’s tone surprisingly nonchalant when describing the phenomenon of hedge funds using 56-to-1 and even infinite leverage in their Treasury repo trades.

In a stable financial system, should the terms “infinitely leveraged” and “hedge funds” ever appear together?

Anyways, here’s how the infinite leverage works.

Say a hedge fund wants to purchase a 10-year treasury. It doesn’t have the dollars to do so but it can borrow dollars from the repo market.

As such, to get this 10-year treasury, it simultaneously borrows dollars from a repo lender, purchases the 10-year treasury, and posts this 10-year treasury as collateral back to the lender for the borrowed dollars! 😮

The lender is okay with this arrangement and is a key enabler of such a transaction.

If the cost of the 10-year treasury and the amount of dollars it can borrow through the repo transaction is the same, then the hedge fund effectively achieves infinite leverage.

In other words, they didn’t have to spend any of their own money to get the 10-year treasury through the materialization of this repo loan out of thin air.

I don’t know enough of the matter to understand how dangerous this type of highly-leveraged repo transactions are for the financial system but I’ve found it fascinating that infinite leverage is not only possible in today’s financial system, it’s a surprisingly common occurrence.

I don’t have a great explanation for why hedge funds would engage in these transactions but if you’re curious, here’s an explanation I’ve found from HackerNews:

“For example, if the yield on a long-term bond is 3% and repo rates are only 2%, you might buy the bond, financed with a repo transaction, and bet that over the term of the repo, the bond’s price will hold up enough to allow you to profit from the transaction. If it is a one year repo, the bond could decline in price by 1% and you would still make a profit because its yield is higher than the cost to finance the purchase.

A more relevant example is if futures are trading rich relative to bonds - say they are too expensive by 1/32th (about 0.03%). In this case you buy the bonds on repo and sell futures against them, expecting to profit when the price gap closes. Of course, 0.03% is not much profit, so you use 50x leverage (which you can easily do on repo, because it is secured borrowing) turning it into a 1.5% profit.”

So there you have it, another minimally publicized but groundbreaking change in the financial system that was brought on as a result of the Great Financial Crisis.

This new system is the product of a combination of the Ample Reserves Regime and the Secured Lending Standard and it works very differently from the system that was in place before 2008. It’s characterized at a high level by:

A significant increase in US dollars and US debt (on the order of trillions of dollars worth), that’s…

Brought on by an extraordinarily liberal policy of printing money and issuing government debt, resulting in…

A Federal Reserve that has become significantly more powerful and important in the smooth operation of the financial system and the economy at large.