Liquidity is Everything

[4 minute read] If you could only focus on one thing to predict stock prices, you should focus on this.

“Liquidity” is a word that’s used profusely in financial media. It’s almost a buzzword at this point. The most popular definition of liquidity is the ease at which one can turn assets into cash at their current market price. In this newsletter issue, we’ll use another definition of liquidity to explain what moves markets. The definition we’ll be using is “the total spendable money in the system”. This is often also referred to as “Global Liquidity”.

Liquidity drives the stock market

When one asks what drives stock market prices, you’ll probably get an answer to the tune of speculation in the short term and economic growth in the long term.

Although this answer has significant truth to it, it’s not helpful. How does one measure speculation in the short term and how does one predict economic growth in the long term?

Here’s a better answer to this question. Stock market prices are driven by global liquidity levels in all time frames excluding the shortest ones. Put simply, as far as the stock market is concerned, liquidity is everything.

Where does liquidity come from?

Given that liquidity is just the amount of spendable money in the system, it comes from a vast variety of sources, from the mundane biweekly pay cheque, to the amount of leverage available to a hedge fund, to the trillions of dollars on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

Central banks, with their power to print money and move national interest rates on a whim, is the most significant drivers of global liquidity.

When the Federal Reserve hiked the Fed Funds Rate from 0 to 5% in a year and started draining its balance sheet to the tune of tens of billions of dollars per month, it was pulling significant liquidity out of the system. On the other hand, when the Bank of Japan started printing trillions of yen to defend its infamous Yield Curve Control policy late last year, it was injecting liquidity into the system.

Global liquidity can also change from smaller scale events outside of central bank policies.

For example, the pandemic student loan moratorium freed up significant cash flow in the US population that was then largely redirected to savings accounts and the stock market. The annual issuance of year-end salary bonuses is a sudden injection of liquidity into markets going into the new year.

It’s also important to view liquidity at the market-level.

While global liquidity could be rising, stock market liquidity could be falling. One simple but impractical example could be rising global liquidity causing money to pour into real estate in the form of mortgages. When this happens, significant money is locked into hefty down payments and meeting monthly mortgage payments that there is less money available for the stock market.

So what?

If you think global liquidity levels move the stock market, then it’s a lot easier to predict where markets are headed. If global liquidity is rising, stock prices will rise and vice versa.

You may say, “oh this is too simplistic, what about interest rates, what about an impending recession? The market surely tries to price these things in and they play a significant role in stock prices?”

From my time observing markets, this is often not true.

Here are some examples:

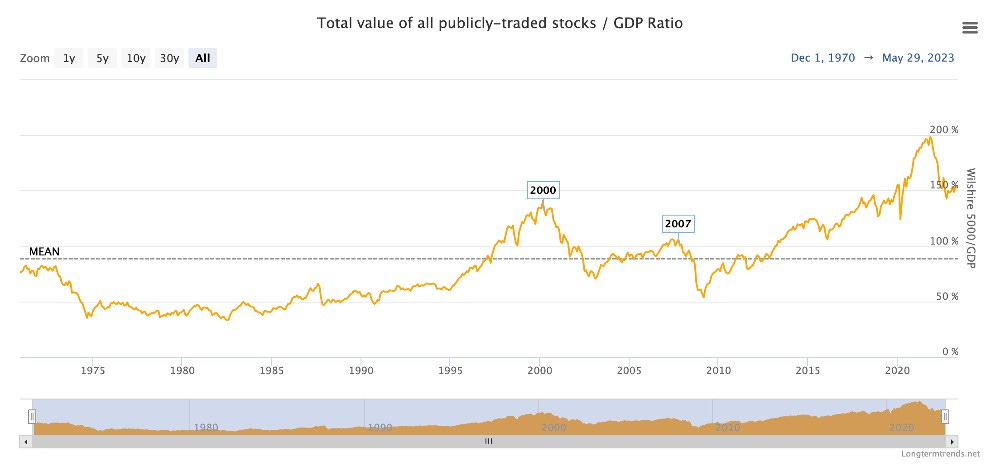

If economic growth drove stock market prices and recessions crushed them, then how the stock market behaved during the pandemic and right now when most economists predict an impending recession serve as stark counterexamples. In fact, the stock market has largely diverged from GDP over the past decade. It has closely followed the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet instead.

Interest rates is the cost of money. When they’re high, money is harder to come by because it’s expensive to borrow which results in less liquidity in the system. When the Federal Reserve raised interest rates from 0% to 5% in the past year, it’d be sensible to conclude that the stock market is done for after such a steep increase in the price of money. Instead, the stock market only fell by 20% from zenith to nadir and is now staging a breathtaking comeback.

How come?

The answer is global liquidity.

Not only is there significant money leftover in the system from companies raising a record amount of cheap debt when interest rates were at 0% during the pandemic, a series of events in the past year significantly boosted global liquidity even as the Fed was draining liquidity.

For one, the Bank of Japan’s torrential money printing to defend it’s YCC policy increased global liquidity. The bail outs of the failing major US regional banks also increased global liquidity. Finally, even as the Federal Reserve was shrinking its balance sheet, the US Treasury under the Biden administration has been spending down hundreds of billions of dollars in the Treasury General Account to postpone raising the debt ceiling.

This explains why, despite the Federal Reserve’s best efforts at pulling money from the system, the stock market is stubbornly anti-fragile and is in the midst of an impressive comeback from the troughs of last fall.

Fin

If you could focus on anything to predict future stock market prices, we think traders are best served focusing on liquidity.

To close off this newsletter issue, here’s a topical and interesting chart that was recently published by Bloomberg.

I agree, that global liquidity is the most important factor of asset prices in the mid term periods. However I am perplexed regarding effects of interest rates... Shouldn't they partially move money from stock markets into bonds? And changes on the margin are the ones driving prices.