Research - Is the Market Efficient?

This article explains the theory behind the popular saying "time in the market is better than timing the market" and examines whether it holds up to scrutiny.

A fundamental axiom of human behavior is that humans love convenience. This goes from trivial tasks like heating up food to life changing ones like investing. Perhaps this is why broad market ETFs and mutual funds have become so popular in the past couple decades, especially in retirement investing. These retirement investment instruments are essentially set-and-forget. Pick a rate at which you want to deposit money, specify how much, and with these simple parameters, the algorithm is ready to start investing for you. For the majority of US workers, this is done through the 401k system; a portion of every pay cheque is deposited in a 401k account and invested in a default retirement fund (typically Vanguard or Fidelity).

This type of investing is popular, not only because it’s extremely convenient, but also because it has been working (in the last 30 years or so, SPY’s annual compound growth rate is 8.25%!) and the zeitgeist of financial advice and literature will sing its praises. “Time in the market is better than timing the market”, as they say. Almost every financial advisor will recommend broad market exposure for retirement investing, with heavy emphasis on US equities unless your time horizon is short, in which case they’d recommend a moderate emphasis on bonds.

The theory behind this is that the market is efficient (Efficient Market Hypothesis, EMH) and unpredictable (Random Walk Hypothesis, RWH). The former states that at any given time, all available information is priced in so the market’s price is fair and correct. The latter is an extrapolation of the future and states that you cannot predict what the market does with all available information at hand. Following these two hypotheses, an investor comes to the conclusion that the current market price is the best price to buy and it’s futile to time the market. Thus the implied best investment strategy is to gradually and consistently buy into broad market exposure.

This article examines EMH and RWH by looking at specific market mechanics, and presents different considerations on market efficiency. Zeitgeists become zeitgeists for a reason, but they also tend to obscure a lot of nuance.

Let’s uncover the nuance in today’s markets.

Rise of Passive Investing

As mentioned above, there’s been a massive proliferation of broad market ETFs and mutual funds in the past couple decades. Money in these funds are considered “passive money”. This is because these funds have very simple mandates and don’t move money around much. For example, some passive funds pick a market sector and keep the fund well balanced for that sector, but they only rebalance occasionally, like every quarter. Retirement funds, like Vanguard’s highly popular target date funds, have a straightforward and predictable asset distribution that gradually shifts from equities to bonds as the target date nears.

The rise of passive investing has been meteoric. According to the Financial Times, the total assets under management for passive funds was about $3 trillion. In 2020, this number was at $15 trillion. Furthermore, a survey by Pensions & Investments showed passive assets under management surged to $20.87 trillion in 2021. Passive is popular.

With so much passive money in the market, the claim is that inefficiencies are bound to arise as a result of the simple mandates of passive funds. They set a general asset distribution goal and occasionally rebalance if the fund drifts from that target distribution. Rebalancing is non discretionary. Any stock in the over-allocated category will be trimmed, despite their quality. This is why you often see market sectors moving in tandem. One day, financial stocks will all drop at about the same percent, while healthcare stocks are up. The next, it’s the opposite. Passive funds move money from sector to sector without discretion for quality within a sector.

Take a Vanguard target date fund for example. When it’s in its “Young” phase, the fund’s mandate is to have 60% of assets in US stocks, about 20% in International Stocks, and the rest in high quality bonds. If stocks moved downwards aggressively in a quarter and caused the fund to be off balance despite inflows, the fund needs to rebalance. When they do, they will broadly sell bonds and buy stocks. There is no discretion for which asset in an asset class is bought or sold. It’s the whole thing, together and at once.

In fact, target date fund rebalancing can sometimes move markets. These funds are the cream of the crop for retirement investing and are unsurprisingly massive. Morningstar estimated that the total assets in these funds stood at roughly $2.8 trillion at the end of 2020. If markets moved aggressively, such as during long periods of high volatility in 2020, a majority of these target date funds would need to rebalance at the same time. When that happens, they move markets. An article from the investment firm Evergreen Gavekal noted an interesting statistical oddity, stating that “the four most recent corrections [prior to October 2020] ended in the last week of the quarter, and three of them ended on the same day – the 23rd.” Although we cannot be sure, this phenomenon is very likely caused by target date funds rebalancing into stocks after a massively down quarter, given the consistent end-of-quarter timing.

This broad and non-discretionary rebalancing behavior of passive funds (which had over $20 trillion in assets under management in 2021) likely creates opportunity. For one, high quality stocks are sold or bought at the same rate as their peers in the same category (vice versa for low quality stocks). A well informed investor can opportunistically, as an example, buy high quality stocks that were affected by non-discretionary selling. Second, a fund’s rebalancing date can be front-runned (e.g. as described in a prior FinanceTLDR article, Trade Idea: XRT and GME). It’s interesting to note that Vanguard is well aware of hedge funds and other active investors looking to front-run its target date funds, and its best defense is obscuring when and how it does its rebalancing. However, no matter how deftly Vanguard conducts its rebalancing, unintentional signals are bound to slip through when one attempts to move billions, or even trillions, of dollars around.

Companies Move Faster Than Money

Another corollary of the wide proliferation of passive funds and their simple mandates is that these funds can be incredibly slow to react when companies broadly shift strategies. A company board or executive team can make a decision to shift the company’s overall strategy in a week, and then start executing in the same quarter, whereas passive funds collectively would need many years to properly reallocate.

Take for example a company that decided to pivot from ICE cars to electric cars. ICE car companies are considered low volatility, low growth, and high dividend stocks, while electric car companies are considered innovative and high growth stocks. When the company is in mid-transition, low growth and high dividend funds that historically owned the company would slowly divest as the company leaves the funds’s mandates by pouring money into R&D while shrinking dividends. At the same time, growth funds will be hesitant to pick this company up, given the historical impression of the company and the uncertainty of their execution quality and speed. This causes companies in mid-transition to have an overly suppressed price. The company straddles the line between passive fund mandates and becomes a misfit for more passive funds than is typical. However, once a transition picks up steam, the company’s stock price can skyrocket as new passive funds aggressively increase exposure to the company. This can be seen with AMD and Tesla. In 2012 to 2016, AMD struggled under $5 but skyrocketed to over $150 in the next 5 years. Tesla, which was struggling with debt problems and execution speed, saw a meteoric rise in its stock price starting at the end of 2019 when its debt problems disappeared with a well-timed China deal, while its execution picked up with the painful but ultimately successful launch of the Model 3.

Observant investors can spot companies in promising transitions and buy at great prices due to passive funds being inefficient at investing in transitioning companies.

Margin Exposure

Another source of market inefficiency is the rise in margin exposure in the market. Margin is essentially the borrowing of money to invest and its use has gradually risen over time as interest rates fall and market volatility decreases (partly from the widespread use of passive funds). For example, a popular long-term investing strategy called risk parity that was pioneered by the largest hedge fund in the world, Ray Dalio’s Bridgewater Associates, heavily relies on a lot of cheap margin to increase exposure to bonds given their disproportionately lower risk than stocks.

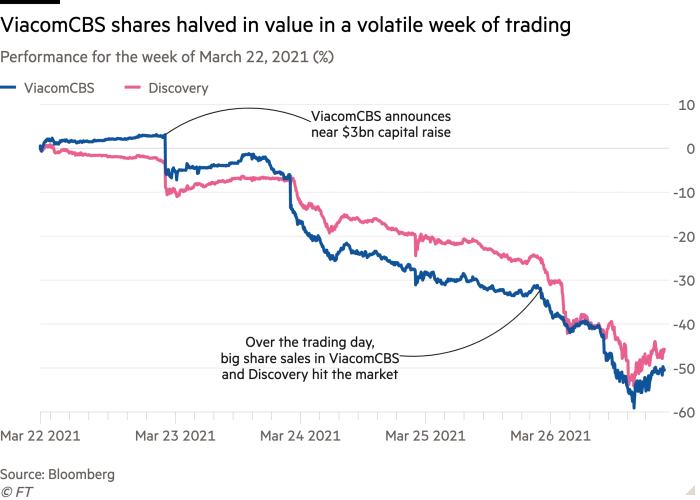

Real estate investors know that the best properties to buy are those from motivated sellers. That is to say the seller is in a rush to sell the property for an exogenous reason and is willing to take shortcuts in pricing the sale to raise cash fast. Well, for stocks, high margin exposure in the stock market creates many many motivated sellers in times of high volatility. During market distress, which often comes with high volatility, funds with margin exposure need to dramatically cut down on their margin use as their collateral falls in value and they become over leveraged. Disastrously exposed funds could also experience violent margin calls and a fire sale of all their assets, such as with what happened to Archegos’s $30 billion fund in March of last year. This is commonly referred to as a margin call.

The more margin the market takes on, the more margin needs to be trimmed in high volatility periods and the more motivated selling needs to occur. This margin-borne market inefficiency occasionally creates unusually deep discounts that opportunistic investors can take advantage of, such as during the COVID crash in early 2020 when SPY fell to as low as $218 from almost $340.

Unnaturally Low Volatility

Finally, as I very briefly touched on above, a side effect of the proliferation of passive funds is the dramatic reduction in stock market volatility. This makes sense, since passive funds don’t move money around much unless they get periodic inflows (in which they buy) or they need to rebalance. Volatility has gotten so low that it’s become a popular strategy to sell volatility (e.g. selling put options) to generate yield. In fact, from the start of 2013 to the end of 2017, the infamous inverse VIX fund (VIX is an index tracking volatility) SVXY generated an incredible 565% return while SPY generated a measly 86% return.

These extended periods of extremely low volatility (largely brought on by passive investing) encourages volatility selling, which then tends to create significant potential instability in the market. Similar to a slowly coiling spring that can violently uncoil at any moment from a minor disturbance (XIV, another ETF that inversed the VIX, violently imploded to zero when volatility skyrocketed in 2018).

This is exactly why there’s been a recent proliferation of hedge funds focused on trading volatility. The core thesis of most of these funds is to be long the stock market, join in the passive investing party, but hedge with volatility. The idea is that volatility exposure is cheap when the market is stable, due to systemic volatility selling, while during market distress, volatility increases exponentially. This makes it a highly effective hedge against the rest of the market.

Volatility contraction is another example of market inefficiency that’s lost in the nuance when following the passive investing zeitgeist.

Fin

The purpose of this article is not to say that passive investing is bad and one shouldn’t engage in it (you should definitely do it for retirement), but that there are always opportunities to find inefficiencies if one peeks under the proverbial hood of the market. Of course, it takes a lot of work and risk to spot and profit from these inefficiencies but for enterprising and ambitious investors, it’s well worth the effort.

If one strictly follows EMH and RWH, one would consider the market as settled. But in truth, inefficiencies slip through the cracks constantly, and the market never settles.