Market Pulse: US Debt Crisis Looms

[5 minute read] A looming US government debt crisis is dominating the market narrative. Here's why.

I’m trying out a new newsletter format to inform readers of the biggest current issues in global markets. I want these updates to be concise, informative, and easy-to-read. Here’s the first piece in the “Big Issues” series.

The Big Issue

The Big Issue right now is that US government debt is getting seriously untenable. The government needs more and more money to fund two proxy wars, with a third brewing in the Western Pacific, while interest rates are sky-high and getting higher.

Short-term interest rates for US government debt have already been quite high for the past year while long-term interest rates remained stubbornly low. This changed in August when long-term interest rates started soaring as well (see chart above).

Interest rates are the price of debt. The higher the rate, the more expensive the debt is. Most of us know that the US government has a gargantuan amount of debt and this amounts to an equally intimidating interest bill. To keep the government funded, it has to issue new debt as tax revenues fall far short of covering the total bill.

If the debt gets too expensive and interest payments become an ever-growing portion of government costs, the government will have to issue more debt at higher interest rates just to cover today’s interest bill. At some point, the situation becomes untenable when the debt becomes too expensive and interest payments engulf the budget. This is known as a debt spiral. If this ever happens (very unlikely, but possible), the consequences are disastrous.

We’re far from a debt spiral, thankfully, but we’ve been on a declining trend for the past few years and this decline has recently accelerated.

We might still be far from a debt spiral, but with the US bankrolling two major proxy wars with a third brewing in the Western Pacific, an ensuing fiscal crisis for the US government is dominating the market narrative.

Needless to say, this is bad for stocks and the economy in general.

The Details

Why is rising long-term interest rates bad?

It’s because short-term interest rates are already high but since the debt is short-term, it falls off the government’s debt burden quickly. In addition, low long-term interest rates give the government continued access to cheap debt through issuing more long-term debt than short-term debt.

When long-term interest rates are just as high as short-term interest rates, the government has no choice but to load up on expensive debt across all maturities. Rising long-term interest rates is not only a sign of weakening confidence in the US government, it’s also a self-reinforcing process as the government’s debt burden gets heavier for the long run.

Why is the market worried about this problem now?

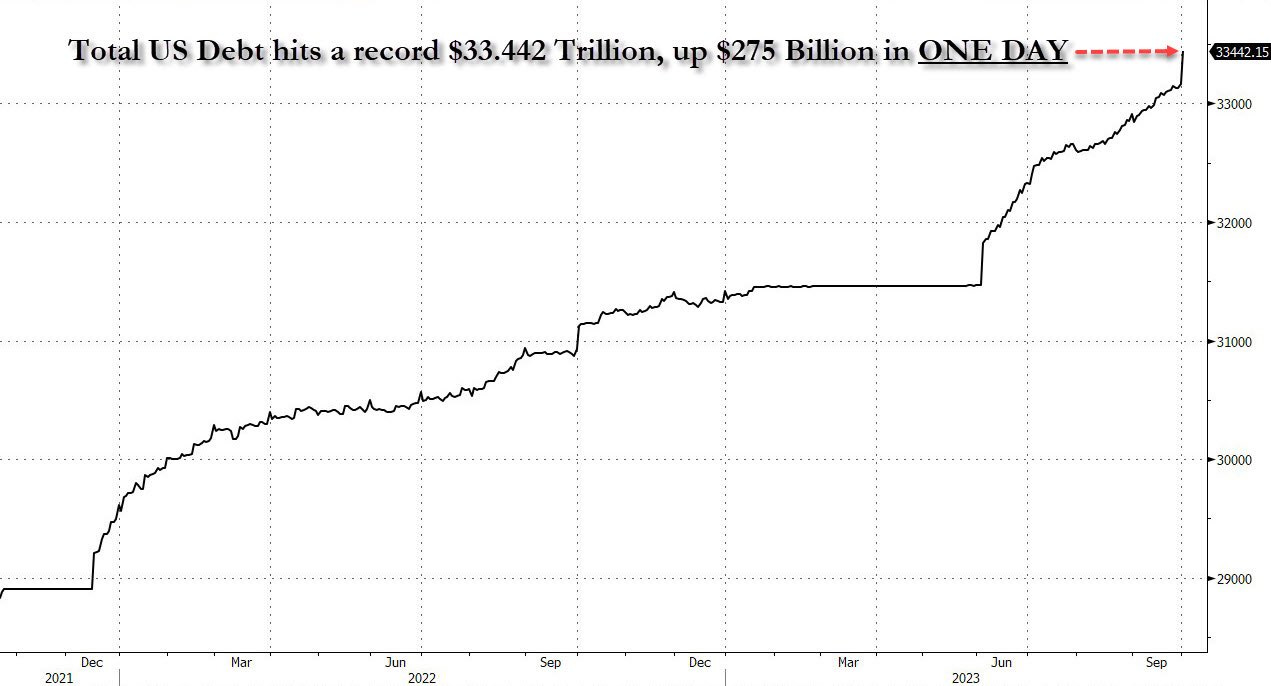

Total US debt is over $33 trillion right now and it rose by $275 billion in just one day earlier this month! Funding the war in Eastern Europe has been expensive and now another proxy war has sprung up in the Levant.

Proxy wars are expensive. Social security is expensive. The market is worried about this problem now because the fiscal decline is speeding up. Rising long-term interest rates is a particularly worrying sign that global confidence in the US is waning.

In fact, just yesterday, Biden asked Congress for $50 billion to address “urgent domestic needs”. This request comes right after a $105 billion request to fund military aid packages for Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

It’s a serious and growing problem, but the situation is not dire today. Why?

If all of the US’s $33 trillion of debt costs 5% annually, the government has to pay $1.65 trillion each year just to cover interest! Thankfully, a significant portion of the debt was issued during times with much lower interest rates and overall interest costs are bearable, for now.

What are the consequences of a debt spiral?

When the debt burden becomes untenable, the government has three options:

Austerity: this means reducing government spending, which could have dire consequences for American society. For example, social security could collapse.

Default on the debt: everyone holds US government debt so if the US defaults, it’s economic doomsday. This is highly unlikely to happen.

Beg the central bank (Federal Reserve) to buy debt: the Federal Reserve has the power to print infinite money to buy US government debt. To be honest I’m unclear what the practical limits are for this money printing (it’ll be related to inflation, though I’m muddy on the details) but the Fed will definitely serve as a powerful stop gap in the event of an impending debt crisis.

The consequences listed above are for the worst case scenario. The more immediate consequences of government budget constraints are falling stock prices and weak economic growth. Government spending is closely tied with rising stock prices and economic growth.

Finally, why are long-term interest rates rising?

The short answer is that the US government is issuing more debt than ever to fund two proxy wars while also having to shore up security in the Western Pacific. At the same time, domestic and global demand for US government debt is weakening.

The Federal Reserve, once a major buyer of US government debt, has stopped buying. Diminishing global demand for U.S. government securities is led by China, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. Notably, China and Japan hold the two largest portfolios of U.S. government debt, with Saudi Arabia not far behind.

China is selling US government debt to prop up a weak domestic economy. They’re also trying to decouple from the US financial system in preparation for possible future actions in the South China Sea. Japan is also offloading US government debt to bolster a domestic economy that’s threatened by inflation as demand for the Yen and Japanese Government Bonds weaken. Saudi Arabia, once a staunch US ally, has seen US relations cool following MBS’s ascension to Crown Prince. The leading Gulf state is now diversifying its foreign investments at the same time its diversifying its foreign allegiances (📉 US, 📈 BRICS).

In general, countries that are not in the best terms with the US have significantly cooled on their demand for US government debt after the total confiscation of Russia’s western assets as a result of the war. Many have started long-term initiatives to diversify away from US assets.