The Only Guide to COVID Inflation You'll Need

Digging into the nuances of inflation to understand whether the current COVID stimulus inflation will stay for the long term.

It seems like everyone's worried about inflation right now. Open the front page of any major financial media publication and there is probably at least one headline related to inflation fears.

And you can't fault them. Prices have noticeably increased. The US government has never been more aggressive with monetary and fiscal stimulus as they have trying to jumpstart an economy locked down by the COVID pandemic.

Jack Dorsey tweets that hyperinflation is coming (source)

"Could hyperinflation become the new normal?"

"IBM CEO says inflation fears could trigger 'some chaos'"

Besides the US Federal Reserve setting record low interest rates and buying trillions of dollars of US government bonds (and even buying high yield corporate bonds for the first time ever!), the US government issued a grand total of $395 billion in stimulus cheques directly to Americans (source). The US is not alone in passing aggressive stimulus policies in response to COVID, the rest of the world was engaged in their own massive and unprecedented stimulus policies too. In fact, Reuters estimated in May 2021 that the G10 group of major economies had so far issued a total of $15 trillion in stimulus in response to COVID.

Economic stimulus responses to COVID-19 outsize those of the 2008 financial crisis (source)

The classic definition of inflation is a rise in prices for a broad range of goods. The classic cause of inflation is a bloated money supply. As such, with trillions of dollars of new money sloshing around, the elevated inflation fears and profuse media commentary must be justified... R-right?

To fear something, we must first understand it, and the classic understanding of inflation misses a lot of nuance that I'll unravel below. Hopefully, this will also alleviate any inflation worries.

Production, Delivery, and Demand

Inflation can be broad and affect most of the prices in an economy, or occur in only a specific set of assets or goods. When the media talks about the recent inflation fears, they're referring to inflation in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI is a weighted average of prices in a basket of goods and is most often used as a rough measure for cost of living. It contains a wide range of goods and services from toilet paper to bacon to rent.

A large chunk of the CPI consists of physical goods that tend to require a global supply chain to manufacture and deliver said goods to consumers. The rise in prices of these physical goods has been the primary focus of inflation worries.

Here is a slightly simplified overview of how the global flow of physical goods work:

How does inflation occur in such a system? Well there are unsurprisingly three main ways:

Production: manufacturers don't have enough capacity to meet demand

Delivery: supply chain doesn't have enough capacity to meet demand

Demand: too many people with too much money wanting limited goods

With COVID, companies and governments expected a massive contraction in Demand as their respective populations are locked down causing a dramatic rise in unemployment. As such, companies rapidly scaled down their operations across Production and Delivery to save money and weather the storm. Governments then injected a massive amount of stimulus to counter this demand contraction. The result was an almost instantaneous increase in Demand while Production and Delivery were both scaled down and needed much more time to scale back up (e.g. it takes more time to reopen a factory or port than to deposit stimulus money in a bank account). This Demand shock caused the price of physical goods, and thus also the CPI, to increase.

Cue inflation fears.

But how permanent is this inflation? If we examine the supply chain bottlenecks created from the COVID Demand shock, we see that most of it is happening in Delivery. The primary issue appears to be ports and the downstream land-based delivery systems and facilities being overwhelmed. Apart from only a few goods (e.g. semiconductors), there are little problems with Production.

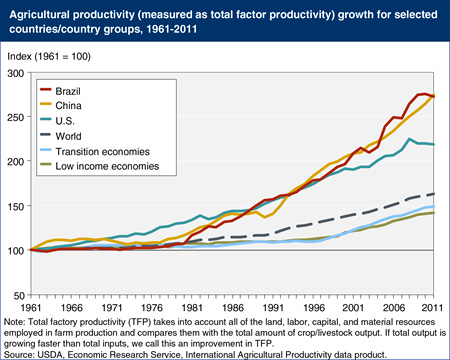

The elasticity and dependability of global production is in part because of the massive (started about a century ago) and ongoing technological boom, coupled with a high level of globalization, that has enabled humans to produce faster and cheaper than ever before across every single category of physical goods. The quintessential example is the rapid increase in global agricultural productivity in the last few decades from innovations in machinery, irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides, and even genetics.

We have so much technological prowess and are so globalized today that Production is hardly an issue. On the contrary, it's actually a major contributor to deflationary worries.

If the primary cause of the recent inflation is Delivery, then I posit that there is actually nothing to fear, since the problems of Delivery are easily solved. For example, major US retailers are already doing it by chartering their own cargo ships to fetch goods from overseas (source)! Economists at Goldman Sachs appear to agree with this analysis, as the firm has recently lifted its fourth-quarter economic growth expectation from 6% to 6.5%, citing stronger inventories and "progress toward unclogging ports" (source).

Where Have the Buyers Gone?

To add on to the argument that the recent inflation is transitory, let's examine the other end of the global flow of physicals goods, the Demand.

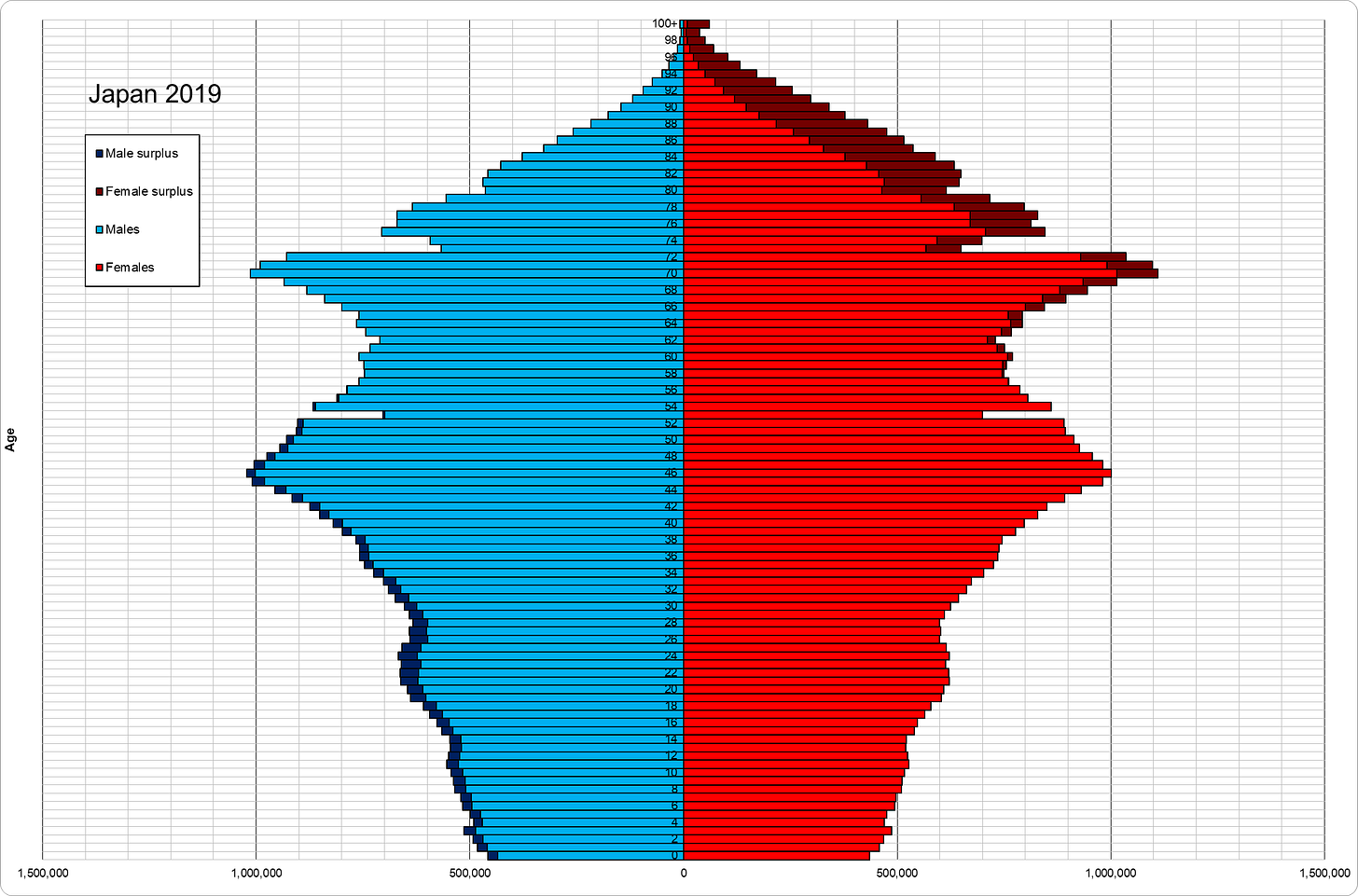

There's a town in Japan called Nagoro that's losing people so fast that its remaining townsfolk have replaced former residents with life-sized dolls. The dolls are dressed up and placed all around the largely deserted town standing along streets or sitting in classrooms. And Nagoro is not the only Japanese town facing a staggering population decline as the Japanese population, like much of the developed world, is aging quickly. Exacerbating the problem for Japan is a massive aversion to immigration.

Photo by Roberto Maxwell

If one were to try to sell children's clothing or toys in Nagoro, the goods will probably fetch a super low price if they could be sold at all. There are simply no buyers in Nagoro.

What is happening to Nagoro is happening at a global scale, albeit very gradually and less dramatically. The population pyramids of most developed nations (i.e. consumption nations) has massively inverted and this is especially true for the low immigration nations of Europe and Asia. Even China's population pyramid is starting to invert.

The Ageing of Japan (source)

The ageing population of consumption nations, coupled with technological improvements and globalization, is causing a massive long term deflationary cycle that we're in the midst of right now. The COVID Demand shock is a mere islet temporarily slowing down this massive deflationary wave.

Doesn't More Money Mean More Buying?

One might argue that the printing of trillions of stimulus dollars must have a profound effect on the CPI, even if there weren't supply chain bottlenecks. This is because a simple application of the supply and demand principle suggests that the more dollars there are, the less valuable each dollar is. The less valuable each dollar is, the more expensive every good is relative to a dollar.

Cue inflation fears.

However, keep in mind that there are many goods in the CPI that have a fixed demand per person. For example, Jeff Bezos probably uses just about the same amount of toilet paper per day as the average truck driver in the Midwest (unless Bezos ate a bad burrito one day or something). The fixed per-person demand of toilet paper is true for other physical goods like food or clothing or cleaning supplies. It's also true for rent.

Without an increasing population, these goods must experience flat or decreasing demand. This also means stagnant prices, no matter how many stimulus cheques Biden sends out. This is a large portion of the CPI that just isn't inflating.

But the extra stimulus money must go somewhere right? Well a lot of it flows into luxury goods, and even more flows into assets that people like to own infinitely. These include stocks, bonds, and real estate. I don't think I need to elaborate further, as the following charts of the S&P 500 and the Case-Shiller Home Price Index speak for themselves.

Chart of the S&P 500 (Google)

Chart of the Case-Shiller Home Price Index (FRED)

Luxury goods and investment assets are not included in the CPI.

What About Venezuela and Turkey?

Finally, one can argue that the frivolous printing of money can result in cases of hyperinflation such as during the Weimar Republic in Germany in the early 1920s, because it is already happening today in many countries such as Turkey, Argentina, and most infamously, Venezuela.

However, the problems these countries face are unique to them in that they have insufficient domestic production, are largely reliant on imports, don't have a currency with global demand, and severely mismanaged their monetary policy by overprinting their domestic currency. This caused said currency to inflate wildly relative to stable international currencies like the US dollar or the Euro, making imports prohibitively expensive. Hyperinflation then ensues.

These conditions do not apply to the three major economic zones of which the three major international currencies reside, namely the United States, Europe, and China.

This is especially true for the United States, given that the US dollar is a global reserve currency. When your domestic importers pay the world in US dollars, there is minimal inflation risk from foreign exchange.

Fin

To summarize, I believe that the inflation we're currently experiencing is transitory and its related fears are overblown. This is partly because supply chain problems following the COVID Demand shock are mostly delivery problems, which are short term and easily surmounted. In addition, population decline in the developed world, combined with rapid technological improvements and globalization, put the world squarely in a massive long term deflationary wave that a few pandemic stimulus infusions will hardly make a dent in.

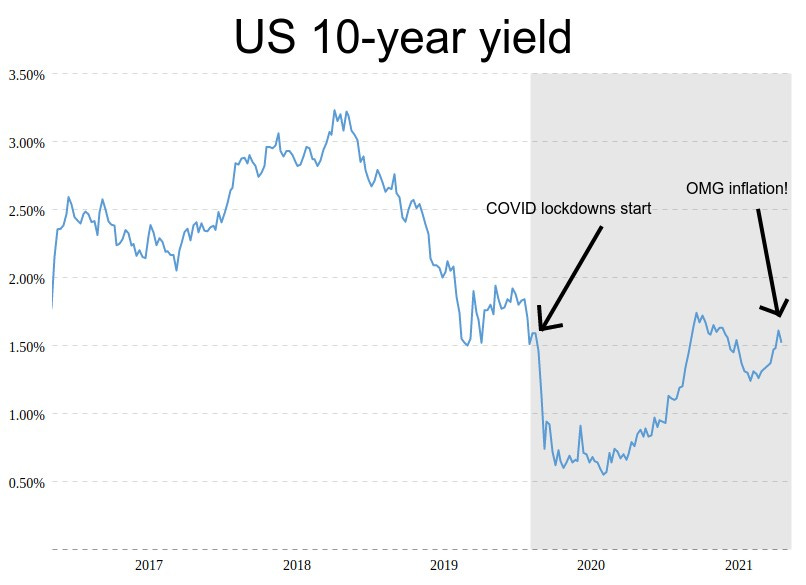

I'll close with a number that I shared in my previous inflation article. The US 10-year treasury yield, which is a good approximation of the global market's collective view of inflation in the next 10 years, is at 1.43% at the time of writing and struggling to go above 1.60%, its level prior to the COVID pandemic. US treasuries is a $22 trillion market and there's hardly a more appropriate and succinct number that summarizes the unlikeliness of long term inflation from COVID stimulus.

US 10-year treasury yield in the last 5 years (macrotrends.net)