Money Printing 101

Quick and easy explanation on how exactly the Fed conducts quantitative easing and tightening.

We often hear mentions of the Federal Reserve doing Quantitative Easing (QE) or Quantitative Tightening (QT) in financial media. Perhaps we’ve heard both terms mentioned one too many times.

Most of us know that both have something to do with money printing, but the details are likely non-existent or blurry.

QE is money printing and QT is the reverse of QE right? That sounds plausible.

This newsletter issue aims to pull back the veil on QE and QT and explain them in a quick, easy, but comprehensive way so that we can inject some substance behind these oft-muttered, vaguely-understood phrases.

You may be wondering: “FinanceTLDR, QE and QE sound incredibly technical, dry, and boring. Don’t you know you’re at risk of putting your readers to sleep?”

To which I answer: “This is a matter of a central bank printing money at the scale of trillions of dollars, how could it be boring?! Strap in and pay attention.”

Two-Tiered Monetary System

Before we dive into the specifics of QE and QT, I have to set the stage and describe the US’s Two-Tiered Monetary System.

This is an interesting one. Did you know that the US financial system actually has two different types of money?

It’s not just one big pool of dollars sloshing around, there are actually two separate big pools of dollars. The financial “adults in the room” tend to gloss over this detail of the system because they think it’s too complicated to know. I don’t think so.

Here’s how the Two-Tiered Monetary System works in two minutes.

Two Big Pools Of $$$

As I just mentioned, there are two big pools of US dollars in the US financial system.

The first pool is meant for Big Financial Institutions; think JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Blackrock, etc. The dollars in this pool are often referred to as Bank Reserves.

The second pool is meant for the rest of us. The dollars in this pool are often referred to as Bank Deposits or Cash. For simplicity, I’ll just call them Bank Deposits.

Three Balance Sheets

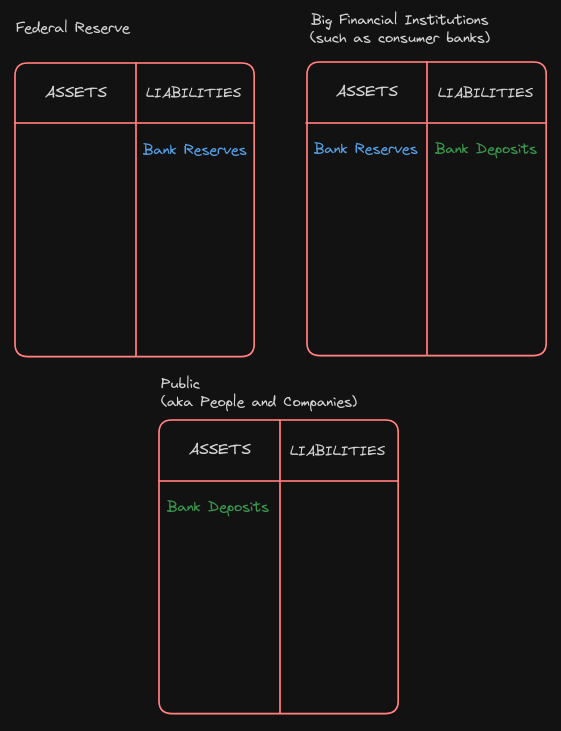

To better understand the two pools of dollars, we can use three simple Balance Sheets to explain them: one for the Federal Reserve, one for the Big Financial Institutions, and one for the Public.

Big Financial Institutions (BFIs) are eligible for bank accounts with the Federal Reserve. These accounts are known as “Master Accounts”. The dollars in these accounts are known as Bank Reserves.

BFIs transact with each other using Bank Reserves, relying on the Federal Reserve to process these transactions by crediting the sender’s Master Account and debiting the receiver’s Master Account.

This is why some people describe the Federal Reserve as a bank for banks (i.e. BFIs).

Similar to how a typical bank’s balance sheet works, the Bank Reserves stored in the Federal Reserve’s Master Accounts are liabilities of the Federal Reserve and assets of its customers, the BFIs.

Many BFIs also happen to be banks, but they’re banks for the rest of us, the Public.

Just like how the BFIs have banks accounts (Master Accounts) with the Fed, the Public has bank accounts with the BFIs.

As such, the Bank Deposits in the bank accounts managed by these BFIs are liabilities of the BFIs and assets of their customers, the Public.

As you can see, from this arrangement, the Federal Reserve has direct influence over Bank Reserves and second-order influence over Bank Deposits. This is why the Fed’s QE and QT operations target the level of Bank Reserves in the system. More on this later.

So there you have it, a quick and dirty explanation of the Two-Tier Monetary System.

But wait, there’s a little bit more. I think this is really interesting.

Armored Trucks and Vault Cash

Big Financial Institutions (BFIs) need to hold dollars as assets to back up its liabilities, the bank deposits. When a customer withdraws money from the bank, the bank needs to have dollars that are immediately available to send out.

As an aside, the ratio of available dollars to bank deposits that BFIs must hold is known as the Reserve Requirement and this is a pretty well-known piece of financial regulation aimed at ensuring the stability of the financial system and reducing the chances of bank runs.

BFIs can hold dollars as either Bank Reserves or Cash In The Vault (Vault Cash). Vault Cash is exactly what you think it is, straight up stacks of green paper.

The Federal Reserve lets banks convert between Vault Cash and Bank Reserves.

When a branch of a BFI needs Vault Cash, they call up the Federal Reserve and make a request for cash. The Federal Reserve receives the request and subsequently debits the BFI’s Master Account and sends a literal armored truck filled with cash to the BFI. The opposite happens when the BFI wants to convert Vault Cash to Bank Reserves.

Quite interesting right? Armored cash trucks!

As an aside, there was an incident on a San Diego highway where an armored cash truck’s door accidentally came loose and cash spewed out of the back of the car. Many drivers stopped and frantically scooped up the cash like it was a game show.

👋 Hello dear reader, if you’ve enjoyed FinanceTLDR so far, consider sharing the newsletter with friends and family.

In the past few issues, I’ve written about:

I have a lot more content planned and am grateful that you’re keeping up with the newsletter.

Also, if you’d be so inclined, you can financially support the work for a very small amount of $7 a month (or $70 a year for the annual deal). Thank you! 🙇♂️

Quantitative Easing and Tightening

Now that the stage is set. Let’s get back to the matter at hand.

Here’s how QE and QT work in the context of the Two-Tiered Monetary System.

QE and QT are tools that the Fed uses to adjust the level of Bank Reserves in the system. Since the Fed, as the sole operator of Master Accounts, has full oversight of Bank Reserves in the system, it makes sense that QE and QT are aimed at adjusting Bank Reserve levels.

QE increases Bank Reserves while QT decreases Bank Reserves.

Quantitative Easing (printing money)

With QE, the Fed buys US treasuries and mortgage-backed securities on the open market by opening a text editor and adding dollars to the Master Accounts of the BFIs that it ends up buying the debt securities from.

Not exactly how it’s done, but at a high level, when the Fed is conducting QE, they’re quite literally just adjusting a database entry to buy debt securities.

Let’s say the Fed buys $100 of US treasuries from JP Morgan through QE. This is how their balance sheets change:

The Fed’s balance sheet expands by $100, using money that it quite literally conjured out of thin air.

JP Morgan’s balance sheet loses $100 worth of US treasuries and gains $100 worth of Bank Reserves.

The result of this is that the financial system has $100 more in liquid Bank Reserves, $100 less in US treasuries, and the demand for US treasuries goes up as supply goes down. When the demand for US treasuries goes up, their prices rise, interest rates fall, and the US government has more room to spend money by issuing more treasuries at a low interest rate.

One can argue that this is a needlessly convoluted way of printing money but money is being printed, nonetheless.

Quantitative Tightening (deleting money)